I’ve spent the last few weeks navigating the U.S pharmaceutical industry and my general instinct with topics that are either intensely confusing or interesting is to write about them. So this is my attempt at unraveling the tangled web of stakeholders in pharmacy and their dynamics with each other as concisely as possible.

I’m hoping to particularly highlight the unintuitive flow of money between these stakeholders, and how it ultimately affects the consumer. It’s precisely the complexity of these economics that is driving waste in the way health plans are designed and run, and it starts with the manufacturers.

The Stakeholders

Pharmaceutical Manufacturers

The U.S is a global behemoth in pharmaceutical manufacturing—46% of global pharma sales in 2022 originated in the US1. The biggest manufacturers in the US are Eli Lilly (founded 1876), Johnson & Johnson (founded 1886), Merck (1891), AbbVie (founded 1888), and Pfizer (founded 1849). The manufacturing and creation of pharmaceuticals is a research-heavy and time-intensive business, so it makes sense that the biggest companies are so old.

These companies all have some stake in four major types of drugs.

Name-brand: These are drugs you find at physical retail pharmacies like CVS and likely what you’re most familiar with. Think Tylenol, Advil, etc.

Generics: These are equally effective alternatives for name-brand drugs but with potentially different inactive ingredients, and are significantly cheaper.

Biologics: These include vaccines and antibodies, and are usually billed in the tens of thousands of dollars.

Advanced therapies: Novel procedures like gene or RNA therapies that commonly target rare and serious diseases; can cost millions of dollars per treatment.

It’s a common grievance that drugs in the U.S cost consumers multiple times what their foreign counterparts pay, and at least part of that stems from the list prices that manufacturers set. The cost to the manufacturers to actually produce these drugs is probably higher in the US than in other countries due to stricter compliance regulations, but manufacturers also have more freedom to control pricing in the US and they take advantage of this to maximize their margins. So at least part of the roughly 229% discrepancy we see between U.S and Canadian drug prices, for instance, can be attributed to manufacturer list prices2.

Wholesalers

Like most wholesale markets, the pharmacy wholesale sector operates on fairly slim margins. The manufacturers sell drugs to wholesalers, who then distribute them to actual pharmacies. They add margins, of course, and tend to charge the highest margins (something like 10-15%) on generics since they’re the cheapest and also sold in highest volume3. Branded drugs tend to be lower (sometimes just 2-3%) in margin but have higher list prices on average. The big three pharmacy wholesalers in the US are AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson and they together account for 90% of American drug distribution4. The manufacturers need wholesalers because drug distribution carries the associated overhead of managing inventory and rapid delivery to tens of thousands of retail pharmacies (compared to a handful of wholesalers). But since they can’t negotiate much with the manufacturers, wholesalers don’t carry much leverage over actual pricing and they’re largely unimportant in the discussion of pharmacy cost containment.

Retail Pharmacies

The wholesalers distribute drugs to retail pharmacies, and for our purposes we’re only going to worry about large chains like CVS, Express Scripts, and Walgreens.

This is where things start to get complicated, because when a patient goes to a pharmacy and tries to purchase prescription medication, health insurance gets involved - more specifically, the pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) that works with your health insurance plan.

PBMs

In the same way that your health insurance networks like Aetna or United Healthcare are supposed to get you discounts on doctor’s visits, PBMs are supposed to get you discounts on drugs.

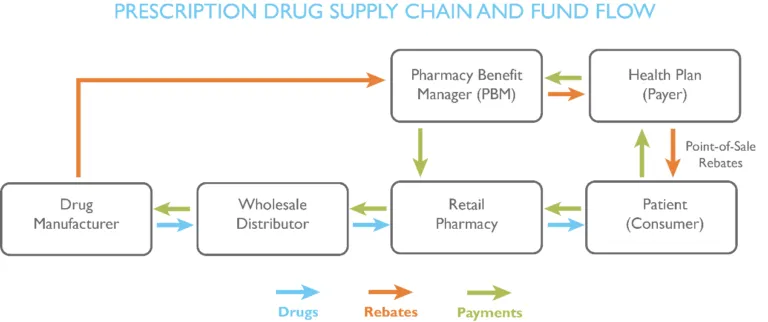

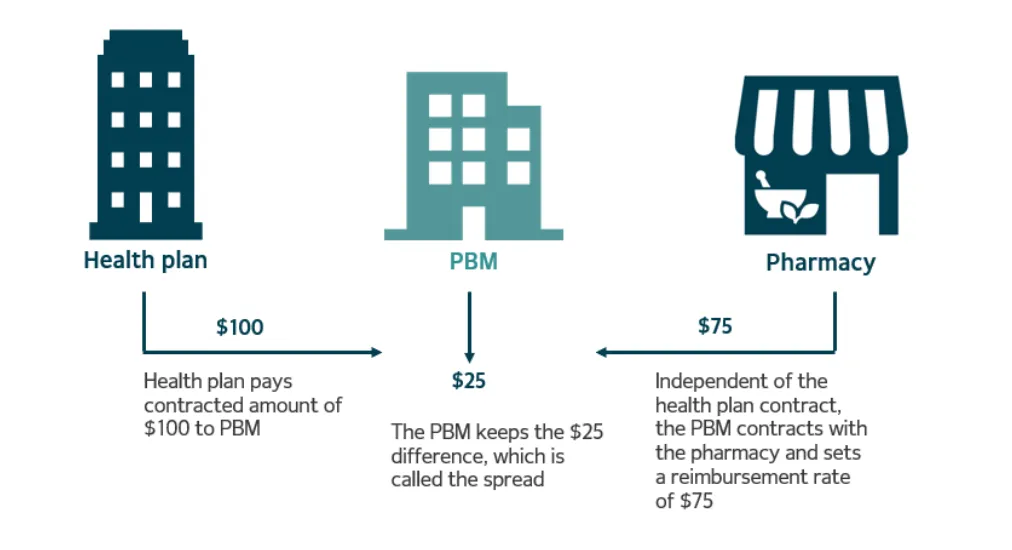

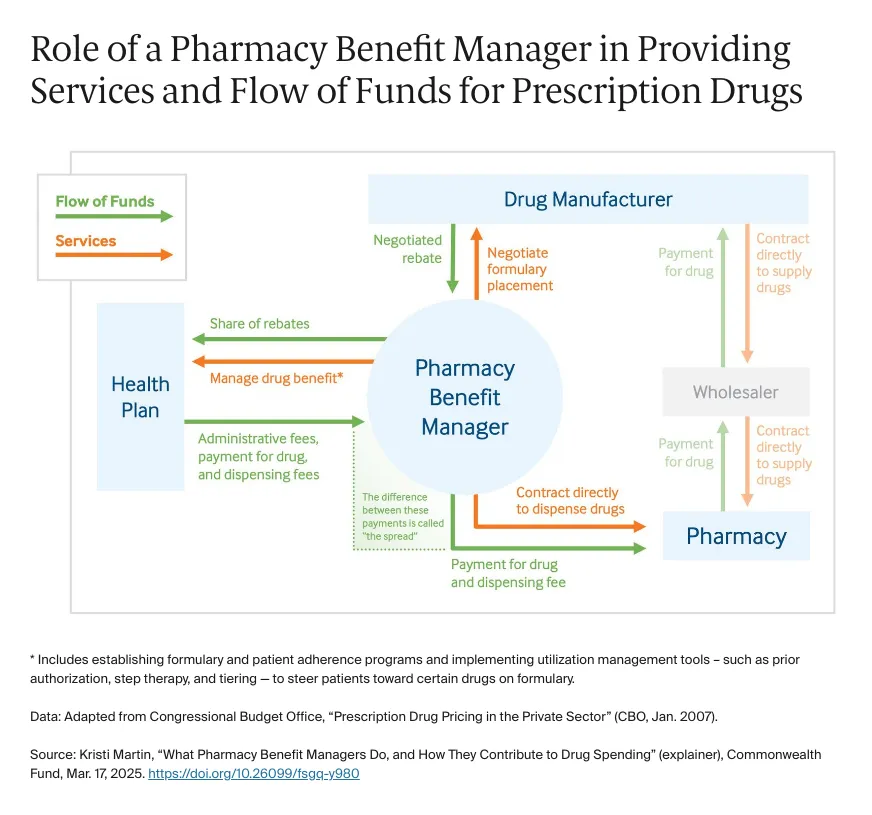

When you buy a prescription drug at CVS, the pharmacist checks your insurance—more precisely, your PBM’s rules—to calculate how much you have to pay (copay or coinsurance). Behind the scenes, it gets messier. The actual cost of the drug to the pharmacy is usually meaningfully higher than what you will be charged, and it’s the PBM’s responsibility to pay the remainder to the pharmacy. So in addition to charging you the copay, the pharmacist also submits a request for reimbursement from the PBM. The PBM then, in turn, passes on that cost to the health plan, and often marks up the amount that is the plan’s responsibility.

So let’s say the copay for a $100 drug at a retailer is $25. The retailer will ask the PBM for $75. The PBM then asks the health plan for $100 and pockets the $25 difference - this is commonly referred to as “spread pricing” and is a major source of revenue for PBMs.

PBMs act as a liaison between manufacturers and health plans, and historically their revenue has been a function of the level of discount they’re able to generate for the employers who ultimately use the health plan.

Health insurance plans maintain lists of drugs that they agree to cover called formularies. Pharmacy manufacturers will pay PBMs rebates for putting a specific one of their drugs on the health plan’s formulary. Getting their drug on the plan’s formulary means patients have better access to the drug and the demand for the drug at retail pharmacies consequently increases, which leads to more sales for the manufacturer. The PBM will often keep a cut of the rebates they get and pass the rest on to the health plan. If you’re thinking right now that rebates sound a lot like bribes, you’re right! What’s worse is that rebates are paid to PBMs as a function of the cost of the drug that was placed on the formulary, so PBMs are incentivized to put more expensive drugs on the formulary so that they’ll in turn get more rebates from the manufacturer. The real issue with this is that the members of the health plan now go into the pharmacy and might have to pay the same proportion of a more expensive drug because PBMs have misaligned incentives.

The trend over the last 20 years has been towards consolidation of retail pharmacies and PBMs, so there are now three big vertically integrated PBM-pharmacies that handle 80% of prescriptions in the US: CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx5. The general idea is if these companies own both the PBM and retail pharmacies, they can capture more of the margins and improve efficiency when pharmacies and PBMs have to communicate.

Closing Thoughts

This is all to say that the next time you’re wondering why drugs in the US are so much more expensive for consumers than their international counterparts, the complexity I’ve outlined here will hopefully point you in the right direction. There’s a convoluted set of regulations and relationships that has created the illusion of value where there is none, and the associated inflation of cost ultimately falls to the end consumer.

PBMs have entrenched themselves as an ostensibly fundamental part of the health plan, but it’s clear that their incentives do not reliably align with those of patients (or even employers). As innovative replacements for the traditional PBM have started to emerge, I’m increasingly challenging the necessity of traditional PBMs as a cost-control mechanism, but that’s a discussion for another time.

Until next time!