So many people in healthcare, including myself, just sit behind a computer and pontificate about how to make the healthcare system better.

I wanted to escape this, even just for a day, so I asked my sister if she could show me around.

My sister has BSN in nursing and two years of experience at Fairview Health as a acute care nurse.

Recorded below are my notes about Julie's job, how her hospital fits into the greater healthcare system, and what problems she finds challenging.

Julie is an absolute boss, featured by the U of M for being a top student.

Zoom Out of System

Fairview is a large academic hospital system in the Minneapolis metro with several campuses. Julie works at the flagship.

The hospital system keeps making headlines for losing money and trying to get acquired, but then facing regulatory delays.

Hospital system consolidation is driving price increases for healthcare nationwide, but from the perspective of Fairview, they need consolidation to survive.

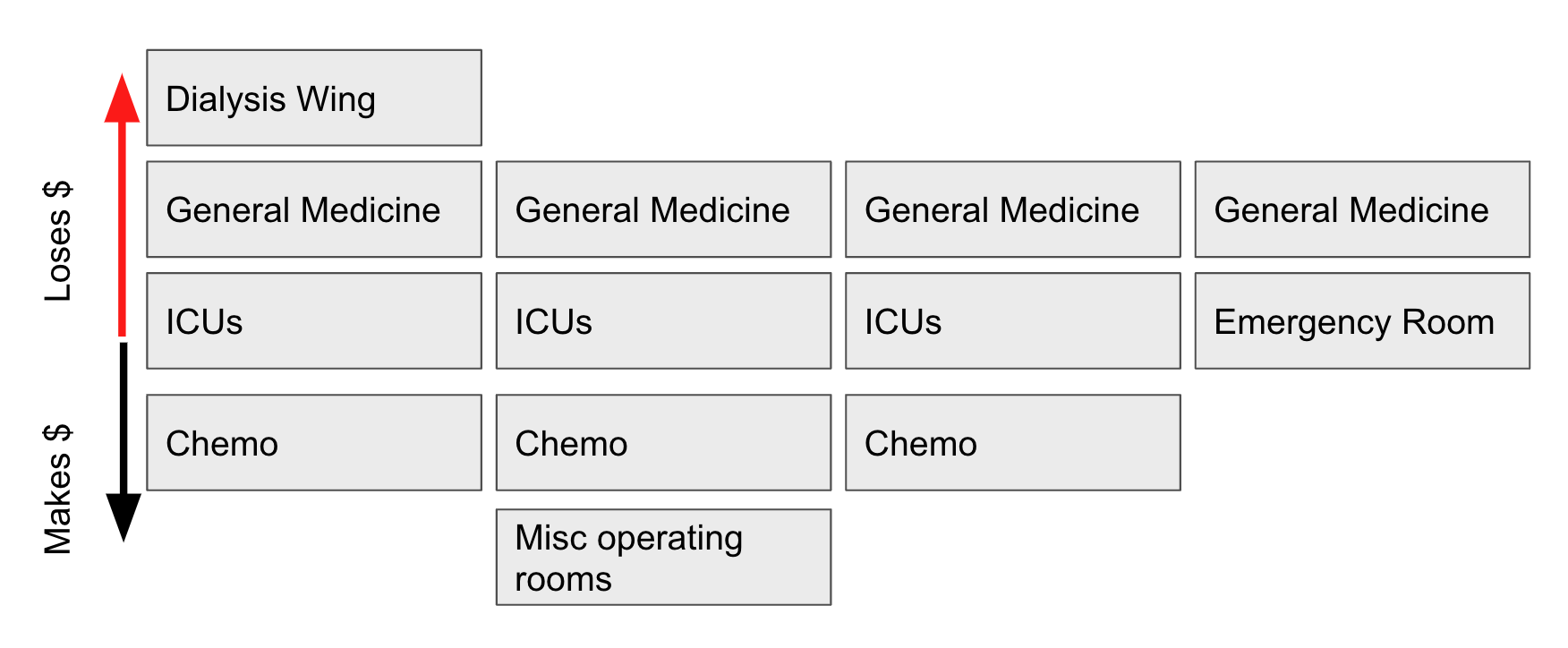

The Fairview Flagship has 4 general medicine wings, 3 ICUs, one ER, one dialysis wing, three chemo wings, and miscellaneous operating rooms.

It's well known to everyone at the hospital that the money makers are Chemo and Operating rooms.

The hospital tends to break even in ER and ICU care.

General Medicine, where my sister works, is the undisputed loss leader.

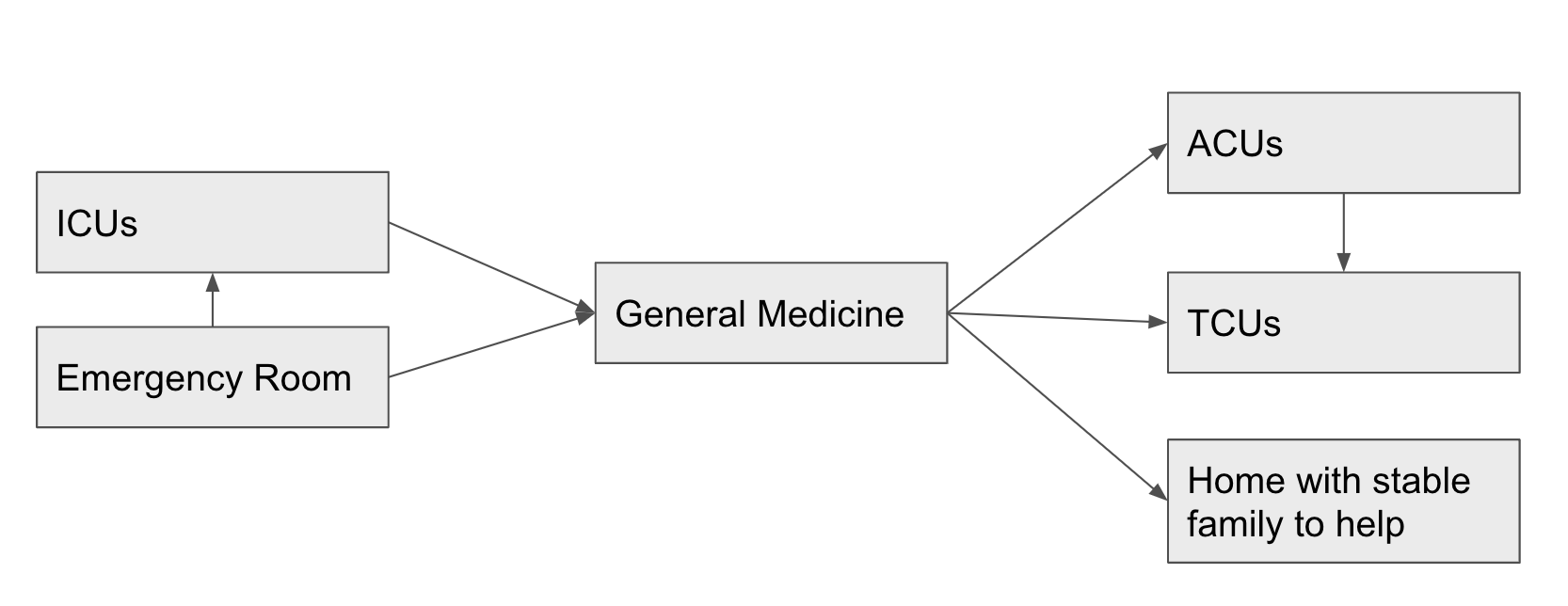

Operationally, the ER refers patients to the ICU units, who then refer patients to General Medicine when those patients are in stable condition with acute symptoms treated.

Chemo wards seem to be on their own track, though I wasn't able to learn much here.

Within my sister's General Medicine ward (similar to other General Medicine wards) there are 19 beds.

The median stay for a patient in my sister's ward is ~1 week. The mean is much higher, though, because some patients can't be discharged.

The hospital can only discharge patients if they are in stable condition and are being discharged to a suitable place given their condition.

Although in many cases, patients can be discharged to their families, many patients do not have families that are able to care for them and help them with their daily medication and activities of daily living.

The traditional option for patients who needed to be discharged but didn't have family able / willing to take care of them is to go to TCUs, "transitional care units". These are essentially skilled nursing homes that offer care less intensive than a hospital.

There are 25 such facilities in the Twin Cities (according to Julie).

The problem is that for the last few years, TCUs have been full and unwilling to take new patients.

Unlike hospitals like Fairview who are required by EMTALA to admit and care for all patients regardless of financial condition, TCUs are able to selectively admit patients. And they typically only admit patients with good insurance.

Uninsured or underinsured patients are left stranded in the General Medicine ward.

At the time I visited, there was one patient who had been in Julie's General Medicine ward for 4 months. He came in uninsured to the ER and had practically recovered under the care of Julie's unit, but was unable to get a placement at a TCU facility.

The Patient Relations department made some mistakes signing him up for insurance, and even when he got insurance he was put in the back of the queue.

Despite his original injuries being relatively mild, the reality of being bedridden for four months had caused this patient to lose the ability to walk.

Staffing, hours, scheduling

Julie's unit of 19 beds has 2 doctors, 7 RNs (including one per shift designated as "charge nurse"), 1-2 APNs, and 1 physical therapist staffed at all times 24/7.

To me, this seems like a lot of labor! Especially considering that for complex procedures (e.g. taking a patient to an operation, discharging and intaking), other floating nurses would come in to help.

3-4 patients per nurse is viewed as a safe ratio of labor to medical need.

Julie works 12 hour shifts three times a week (36 hrs/week). This is not as many hours as I had thought that she worked. She is paid ~$50/hour which is pretty good pay in Minneapolis. People felt very satisfied with pay and benefits when I asked. Their biggest concern was the difficulty of the job compared to cushier jobs as telemedicine NPs and/or nurses at more suburban clinic settings.

Nurse scheduling seemed pretty broken, as nurses routinely complained about how long their shifts were, how they had inflexible schedules, and how last-minute cancellations caused them to work overtime frequently.

Billing/Insurance/Etc

The nurses and doctors in Julie's unit did not know much about insurance. Whenever they get questions about billing / insurance they refer patients to the Patient Relations unit.

Patients do regularly decline medication due to financial concerns, although nurses don't typically get questions about specific prices or financial options. Nurses do not know the answers to these questions anyways.

The staff knew that I worked for a startup insurance plan, and I asked them their tips on how to build a good insurance plan.

Their complaints with insurance were almost entirely complaints with Medicare specifically. They also had concerns with certain types of physical therapy not being covered, and low reimbursement rates for outpatient nursing that they believed to be clogging up their General Medicine ward (as previously discussed) by restricting supply of TCU facilities.

Roles and Responsibilities

The shift I was at, Julie was taking on the role of Charge Nurse, although she had only begun to take this role recently (after 2 years of experience) and it was still a minority of her shifts. The roles of everyone on Julie's wing is approximately:

1 charge nurse: Attend to the desk, phone, EMR. Handle scheduling interruptions, requests from other departments of the hospital, and assist in acquiring resources and knowledge when an unusual situation comes up and another nurse needs consultative assistance. Keep spirits high.

6 floating RNs: Each RN is assigned 3-4 patients they have to monitor. Most of their time is spent administering routine medicine and doing routine tests (stool sample, blood test, etc). I was shocked by how many medications patients generally take, it's maybe 2-3 per hour per patient. There are procedures around each type of medication being administered that causes just administering medication to take a while. Nurses also assist with ADLs (activities of daily living), transporting patients, and talking through care with patients.

1-2 APNs: These lower-trained nurses assist patients with ADLs (activities of daily living) including washing, bathing, going to the bathroom, transporting themselves, and eating.

2 doctors: It was incredibly unclear what the doctors did, except for legally write the opioid prescriptions that over half of patients were on. The doctors would also do most of the talking through care options with patients and interpretations of charts. Julie made it clear that she often notices and corrects huge mistakes that doctors were about to make. These mistakes include prescribing a medication the patient is allergic to, missing conditions that would lead to alternate diagnoses, etc.

1 PT: The physical therapist would go around and do 30 minutes of exercise and moving with patients one by one. I talked to this person the least.

"The Tech"

I think Julie had told her co-workers I was a tech guy so they kept trying to show me the ways in which tech came into their job.

My takeaway is that the tech was pretty smooth and not that broken.

Medication delivery

Before administering a drug, nurses scanned both the drug container and the patient's wristband. This automatically noted in the EMR the drug delivery. It also was designed to catch mistakes.

The machine that dispensed controlled substances to nurses was also sophisticated and involved scanning and careful tracking and accounting. It worked smoothly.

The EMR

The other "tech" features the nurses showed me was the EMR. It was pretty cool, and showed a lot about patients and the medications they were on (including linking to schedule), and their monitors / test results.

As charge nurse, Julie would glance at these monitors every once in a while to see that everyone was stable. She said she often noticed things doctors didn't on those monitors.

Data privacy

Nurses had their share of complaints about how long their passwords had to be for things, how difficult it was to try to filter patient medical data out of certain conversations, etc.

Julie claimed the EMR would let her look up anyone in the hospital system's data, but that if she saw information that she didn't need to see she would be monitored and questioned later about why she snooped around.

The staff was medium-compliant with data privacy, at least according to by-the-books standards. Although I signed some documents upon shadowing her unit, I was not supposed to be able to see patients charts although nurses showed me patient charts many times.

There was also a hilarious incident mid-shift when another department called Julie to say that they had been hearing everything that was said in one of the patient rooms through their phone speaker. The IT team was called, who recommended unplugging and replugging in the physical wall-phone causing the issue. This resolved the issue.

There was some rumbling about "was this a HIPAA thing, should we report it", and "nah, it's fixed, we didn't say that much about the patient's medical data while the phone was unknowingly broadcasting us across the hospital, it's fine".

The "Problems" as I See Them

Problem #1 : TCUs

Everyone (me, nurses, billing, hospital mgmt, patients etc) would agree on is that patients needing TCUs can't be released to TCUs. I discussed this above.

The daily issues this causes are huge. Various ICUs will call Julie's unit begging for them to open up a bed, but Julie's unit has no more beds and can't open up beds because the occupants of beds can't reserve space at TCUs.

The quotes I heard about this astounded me:

"The ICU nurses call in tears, sometimes, and ask if there's anything I can do. There's nothing I can do."

"The ER unit has people in the hallway. Imagine being a patient in the hallway, asked to poop in a bag without privacy. That's happening downstairs because we can't open up beds"

I come from a work culture that values high-urgency, so take this with a grain of salt. I did not see many nurses that truly felt like this was an issue they could control. My sister said that young nurses generally operated with more concern and emotion about the problems of the hospital, whereas older nurses accepted these problems as out of their control.

I was shocked that there wasn't someone yelling about these problems, or otherwise thinking about drastic and creative solutions. But everyone was treating it as just an accepted thing that they were clogging up care for upstream emergency patients. There was a significant amount of internal politics I observed over how different wards transfer patients and when.

Her unit did not like to be pressured to take patients from the ICU wards.

Problem #2: Overmedication

Half of patients were on opioids, and the median patient had 10 separate prescriptions.

A lot of the "care" a patient received was transactional -- receiving a prescription or a medication dose -- instead of more wholistic care.

Managing all the prescriptions a patient was on became a huge headache, both in terms of the schedule the nurses had to be on to do the injections and the potential allergies and complications opened up by the combinatorics of double-digit prescription regimens.

I am privileged and never in my life have taken a prescription medication. I am also afraid to, fearing dependence, side-effects, and high costs. I don't think I am wrong for fearing these things and biasing against medication.

There is no bias against meds in the hospital, though, let me tell you. There is a sense by many doctors and nurses that the more medications a patient has the more care they are getting.

The exception to this general rule is that young nurses (<3 years out of school) are generally appalled by the amount of opioids going into patients' brains. Older nurses openly told me "opioids make patients easier to deal with" but younger nurses were more conflicted.

Problem #3: Certifications

It is viewed as completely natural that the certifications a person has are what leads them to be able to carry out their role. I expected nurses to be a bit miffed about how doctors are able to do stuff they can't do for their patients, but in general the RNs saw themselves as a happy middle class. They were defensive of their ability to do things that LPNs were not able to do.

I asked, after seeing the general depressed mood of patients, "do you ever have people come by to just cheer patients up?". The response was "Oh, like Certified Nurse Coaches?". I was shocked this was a job that needed certification. Everything in the entire hospital needs extreme certification.

One of the more senior nurses was studying to be a Nurse Practitioner by taking night classes. I asked her what she thought she had to learn from her classes that she didn't absorb in 18 years on the job as an RN. She seemed shocked by this question, and pretty much only answered that she needed an NP credential to be able to be a tele-health nurse which she wanted to do for the less stressful environment.

Takeaways

I think nurses have a lot of insight on the system. They have to deal with all the broken parts that us people behind screens make up and enforce (or think that we enforce, really).

I trust nurses, and I don't trust many people in the healthcare system. And I don't think I'm alone in uniquely trusting nurses. I think there is a lot of value to unlock by helping nurses expand their impact.

Sure, doctors are boots-on-the-ground as well, but there is something about nursing culture that is truly patient first. Doctors feel competitive, sales-y, arrogant, abstracted. Nurses just feel real.