My first post in this series looked at the moral implications of centralized healthcare decision-making, dubbed “The Algorithm”. That post explained why an obsession with healthcare data leads to oppression and moral degradation. This post aims to show why that oppression isn’t even markets-wise effective or efficient, anyways.

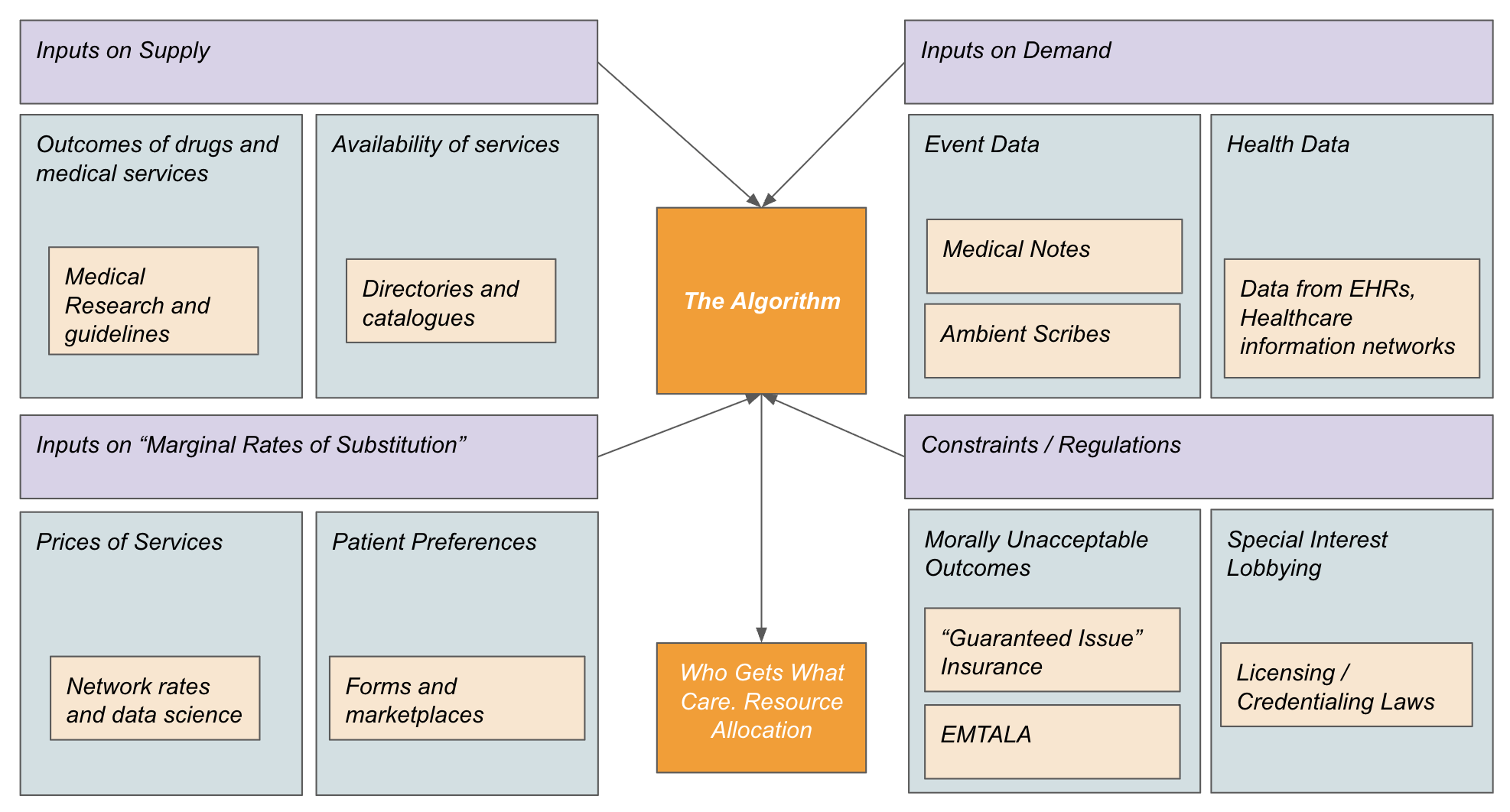

The Algorithm was defined in Part I:

The Algorithm is a mythical input-output information system that takes as variables all medical and financial information about a patient, all cost and quality information about all providers, and dictates a morally and economically optimal way of caring for and paying claims on behalf of that patient.

While Part I analyzed this system from a moral perspective, this post analyzes The Algorithm from a markets perspective.

Those that know me know that I am a diagrams person. A good diagram for how “The Algorithm” is supposed to work is drawn out below. All information gets transcribed and encoded appropriately and then sent into The Algorithm. Only then, under the purview of The Algorithm, does data actually get processed and turned into decisions about what resources to allocate to whom (e.g. which claims to approve).

Please take 90 seconds to zoom in your screen, puff your cigarette, spit out your coffee, curl your eyebrows, and reflect on the above diagram.

The Algorithm is of course the claims process. All resource decisions in healthcare are governed by the claims process: namely which claims will be approved at what coverage level under what conditions. Almost all other algorithms in healthcare (such as scheduling algorithms at hospitals) are designed to optimize an interaction with the claims process, e.g. “The Algorithm”.

We have been conditioned to think that The Algorithm is efficient because the processing steps that it does are all based on sound statistics and logic. This may well be true: given the inputs The Algorithm does get to the right outputs.

So why then does The Algorithm suck? Why does my doctor know better than my insurance? Why does the insurance network get a bad discount?

The Algorithm is inefficient because it does not have nearly enough information available when making decisions. It only sees a small subset of the information available. Despite processes, laws, and technology that have been optimized to gather and distribute information, only a small percentage of the information needed to build an optimized algorithm is actually collected and transmitted to the processor.

Information not available to “The Algorithm”:

Non quantifiable information about preferences and quality (e.g. I don’t mind traveling to Florida for a surgery, I have family there).

On-the-ground supply constraints and excesses (e.g. does the pharmacy have my med right now?).

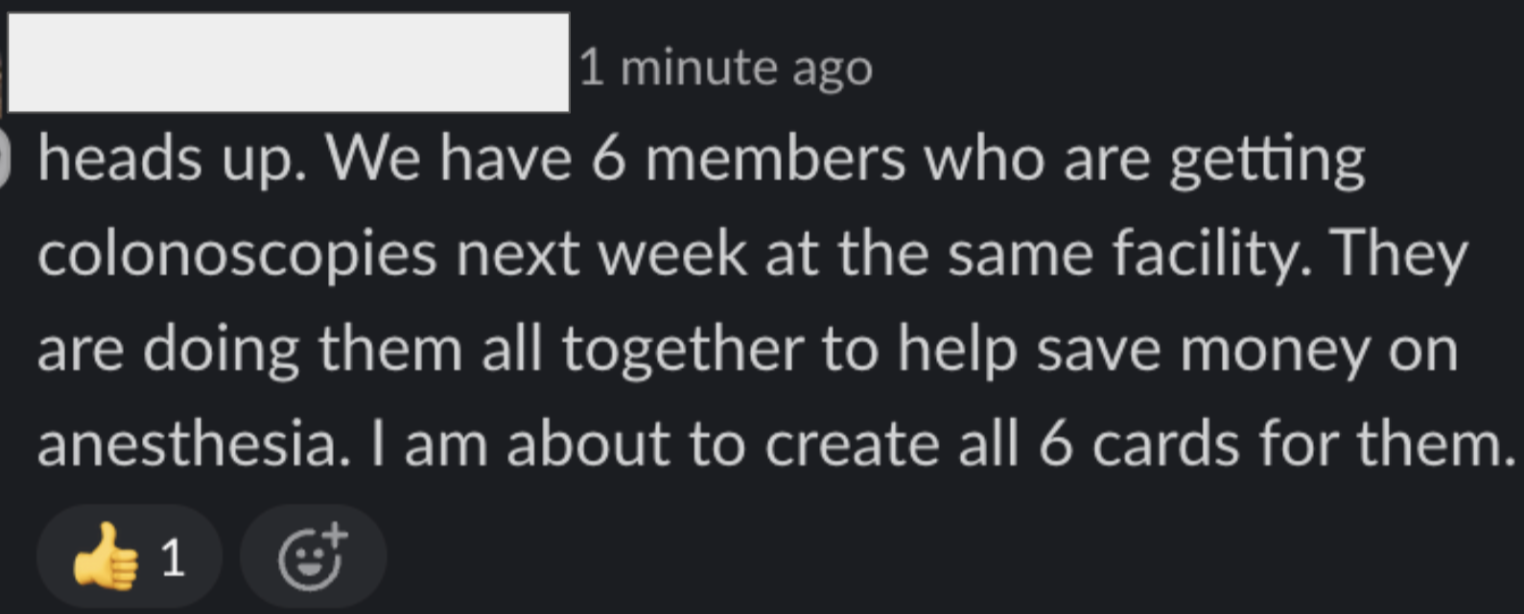

Creative solutions to problems (e.g. there are 6 people who all need colonoscopies and can get a discount if we put em all back-to-back-to-back).

Relation to Theories of Communist Economics

This is not my thesis, and this situation is not new. Roughly, this is the same question that was considered in the mid-twentieth century when economists were trying to theorize about the efficiency of centrally-planned, communist economies. At that time, the prevailing wisdom was that centrally-planned economies could be more efficient by avoiding a lot of the pitfalls of competition: namely overproduction and insufficient cooperation.

The field of econometrics had just been born, and people were starting to technically understand and measure the relationship between inputs and outputs in economics. It seemed like with technical knowledge and centralized control wealth could be created scientifically. Just get all the inputs of production into an algorithm and let the computer make resource allocation decisions.

Friedrich Hayek’s 1945 essay “The Use of Knowledge in Society” is regarded as one of the greatest economic papers of all time because it successfully predicted that communism would fail. The crisis the article analyzed was regarding Central Planning: in particular whether Central Planning was efficient. From Hayek’s own words:

“This is not a dispute about whether planning is to be done or not. It is a dispute as to whether planning is to be done centrally, by one authority for the whole economic system, or is to be divided among many individuals.” - Hayek

Hayek identifies knowledge dissemination as the limiting bottleneck to planning. This insight is consequential because if knowledge dissemination (rather than processing) were the limiting bottleneck for optimizing resource allocation then it means that individuals with local knowledge of a situation could make better resource allocation decisions than a central authority could, because on-the-ground information could not be fully communicated to the central authority.

If Hayek could speak 2025 lingo he would say that individuals and their market-driven instincts help to compute the optimal resource allocation solution for society. They don’t do this by knowing the exact implications of all of their actions but by making optimization decisions based on knowledge available to them but perhaps not widely known and not easily communicated to others.

Anyone who has actually done any bit of real work in the world knows this to be true. It is simply not efficient to ask your boss to help you make every single decision. The cost of communicating what you know to your boss is time-consuming and doesn’t have perfect information fidelity. Instead, a good boss will trust their employees to make good decisions knowing that they have the most context and information.

“It follows from this that central planning based on statistical information by its nature cannot take direct account of these circumstances of time and place, and that the central planner will have to find some way or other in which the decisions depending on them can be left to the "man on the spot." - Hayek

Hayek though did argue that one type of information was critical to the “man on the spot” making decisions: prices. This is worth repeating. Decision-makers need information about prices. Prices. PRICES. PRICES!

“It is more than a metaphor to describe the price system as a kind of machinery for registering change, or a system of telecommunications which enables individual producers to watch merely the movement of a few pointers, as an engineer might watch the hands of a few dials, in order to adjust their activities to changes of which they may never know more than is reflected in the price movement.” - Hayek

Prices are how individuals get accurate information about available resources from the outside world without communicating with an all-knowing central authority. If Hayek existed in our time, he would say that prices are like statistical weights in a machine learning model that keep track of edges between nodes that are all operating to solve some optimization problem.

A high price for a material or service roughly means that it is scarce and it would be better for society if people who could find substitutes for that material or service would do so. It is fortunate that profit is a good motivation for people to consider their substitution options. Importantly, the price is really all the person needs to know to help society optimize its resource allocation. The person does not have to know why the material or service is scarce, just that it is expensive.

“Attention is All You Need”? More like “Prices are All You Need”.

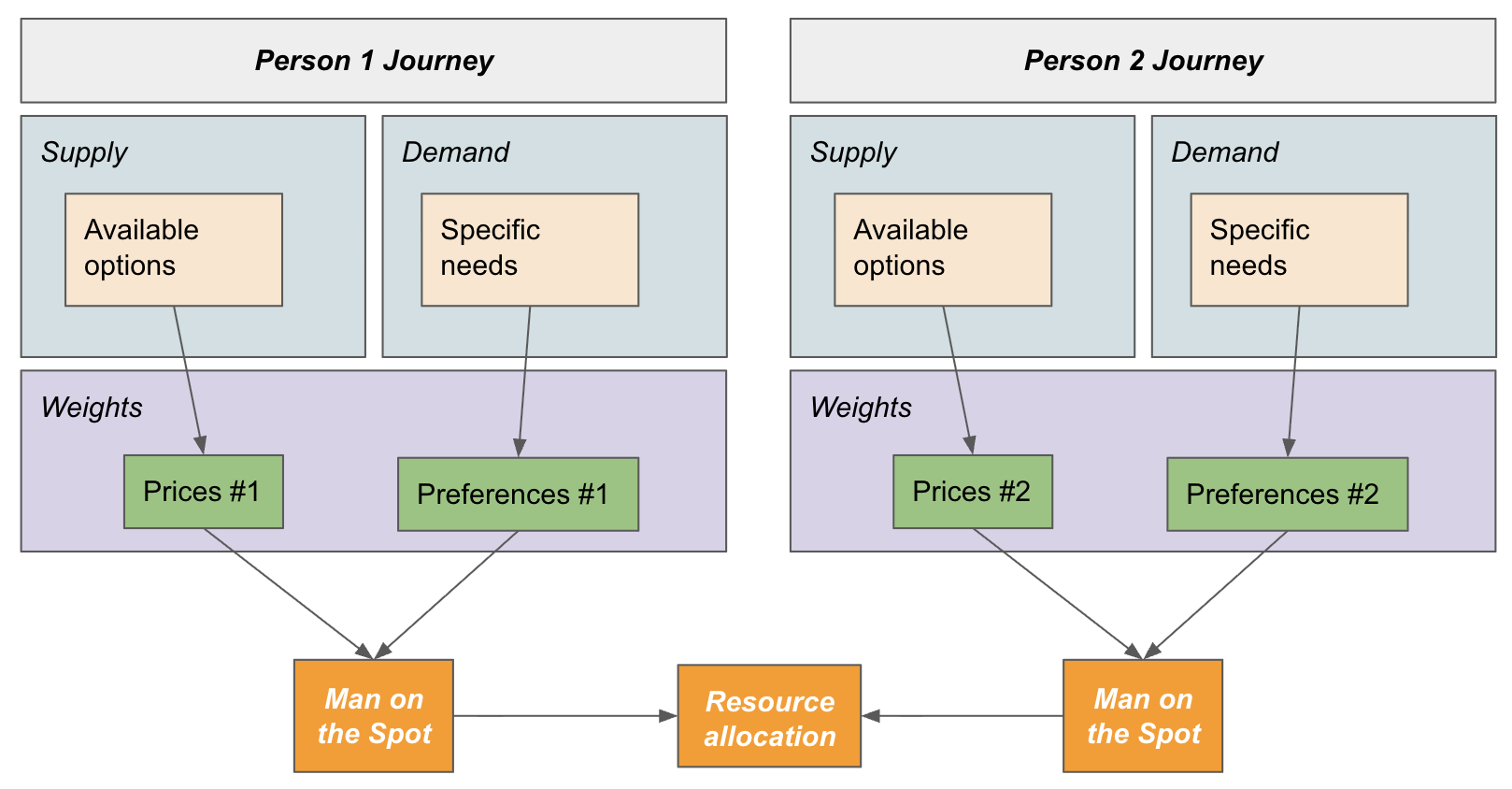

Overall, the a price-based model of the world computes the solution to the optimization problem defined by the preferences of all individuals and the rates of marginal substitution between healthcare resources. It does this by relying on a bunch of local maximizer decision nodes (real human beings) that each independently consider preferences and prices.

The biggest difference between this diagram and the first diagram of The Algorithm’s Central Processing is that Prices and Preferences are much better considered in the second diagram because they are observed on the ground rather than from above.

Returning to Healthcare

The Algorithm in healthcare assumes that it is even possible to get all relevant information to feed into the data-driven models insurance plans and hospital systems create.

They believe that it is possible to

Quantify and measure every single healthcare interaction

Algorithmically know the price of every possible intervention

Agree on an optimization function for how to proceed with decision-making

Deal with unexpected changes and new information

In reality, as anyone who has remotely managed a healthcare process knows: it is fairly impossible to make decision-making into a pure process. There are a lot of times when decisions just have to be made. The best person to make these decisions is the person with the most context: the “man (or woman) on the spot”.

In healthcare, physicians oftentimes have to make decisions that they cannot fully justify in an algorithmic manner, but this does not mean the decisions are wrong. It just means that the “algorithms” that are supposed to be making decisions might not be taking in all available data.

It is not only immoral but also inefficient to expect centralized algorithms to make decisions on patient care. Instead, decisions should be made by those that have actual context and circumstantial knowledge which can never be fully modeled by The Algorithm.

“If we can agree that the economic problem of society is mainly one of rapid adaptation to changes in the particular circumstances of time and place, it would seem to follow that the ultimate decisions must be left to the people who are familiar with these circumstances, who know directly of the relevant changes and of the resources immediately available to meet them. We cannot expect that this problem will be solved by first communicating all this knowledge to a central board which, after integrating all knowledge, issues its orders. We must solve it by some form of decentralization.” - Hayek

The “Man on the Spot” (a care navigator or doctor) is able to really deeply understand specific prices and preferences in a way The Algorithm would never: perhaps they know about a local provider who has unpublished cash discounts or they know that the member has a family that can help them travel a bit further to an MRI center that will get them seen faster. These doctors are already managing referrals, what if the claims process was built on top of those rails?

Any strategy short of radically trusting and holding accountable doctors and local care navigators with the costs of care runs into communication bottlenecks and algorithmic pitfalls.

You Can’t Make Doctors Think About Prices, Though. That’s Immoral!

The default belief in healthcare is that doctors shouldn’t think about prices, for this would somehow taint them and turn them into “the bad guys”. I’ve always found this argument to be completely absurd. Of course doctors should think about prices, prices matter and reflect real things. Patients as a class of people do care about prices and overall would want a healthcare system with lower prices. It is not only insurance companies that care about prices, and the inefficiency of the current system largely stems from not listening to doctors about how to find good prices.

Hayek’s most prescient remark regarding this idea is when he tries to justify the importance of price decisions by observing that managers complain about prices all the time. If the job of a good manager was simply to implement a plan and not care about prices, you wouldn’t see this type of complaint:

“The very strength of the desire, constantly voiced by producers and engineers, to be able to proceed untrammeled by considerations of money costs, is eloquent testimony to the extent to which these factors enter into their daily work.” - Hayek

Indeed, everyone hates being price-constrained in the service of their customer. Everyone would prefer to have access to other people’s money to serve their customer. But it is this price-constrained decision-making that universally leads to efficiency and autonomy in the non-healthcare, non-communist economy.

We are at an impasse in healthcare. Doctors and caregivers complain about losing control over their work and their craft due to subjugation under the insurance regime (“The Algorithm”). Yet, simultaneously, many doctors view prices as something that they don’t want to ever have to think about.

It is not possible to have it both ways: prices matter and consumers (through their insurance plan) do want lower prices. Finding good prices for medical goods and services is a computationally difficult task. The top-down socialist approach to healthcare argues that individuals should not make decisions since decisions should all be made centrally. This is not the only way: the other path is for individuals to care about and be accountable to prices as they make decisions for themselves as patients and for their patients (as caregivers / healthcare advocates).

Afterward: Feasibility

Even accepting that complex markets like healthcare function better by relying on “local” computation through price decision-making, is this feasible for healthcare?

I am not sure. Admittedly it’s an uphill battle. There is something about the psyche of medicine that seems confusingly attracted to the idea of an algorithm (even an inefficient one) making decisions for doctors. It was not the government or insurance companies who built the Residency Matching Algorithm, or defined CPT codes. It’s been doctors themselves who’ve chained themselves to this rock.

The first step towards freedom from “The Algorithm” of a distant insurance plan is for doctors and patients to be equipped to know the prices of the services they consume and recommend and be willing to make price tradeoffs. This is completely doable, as healthcare does not have to be priced in a confusing way. There are innovative groups of doctors deciding to do just that. Some of my favorites are listed below:

Solstice Health (Wisconsin) https://solsticewi.com/surgeries/surgery-pricing/

Surgery Center of Oklahoma https://surgerycenterok.com/surgery-prices/

These practices understand that part of their value-prop to patients is their price and they have designed their operations to remove expensive administrators.

Will other practices follow-suit? Or will doctors at health systems continue to submit to The Algorithm despite knowing that it isn’t making the right health or financial decisions for their patients?

Shameless Plug: We are Hiring Software Engineers in NYC

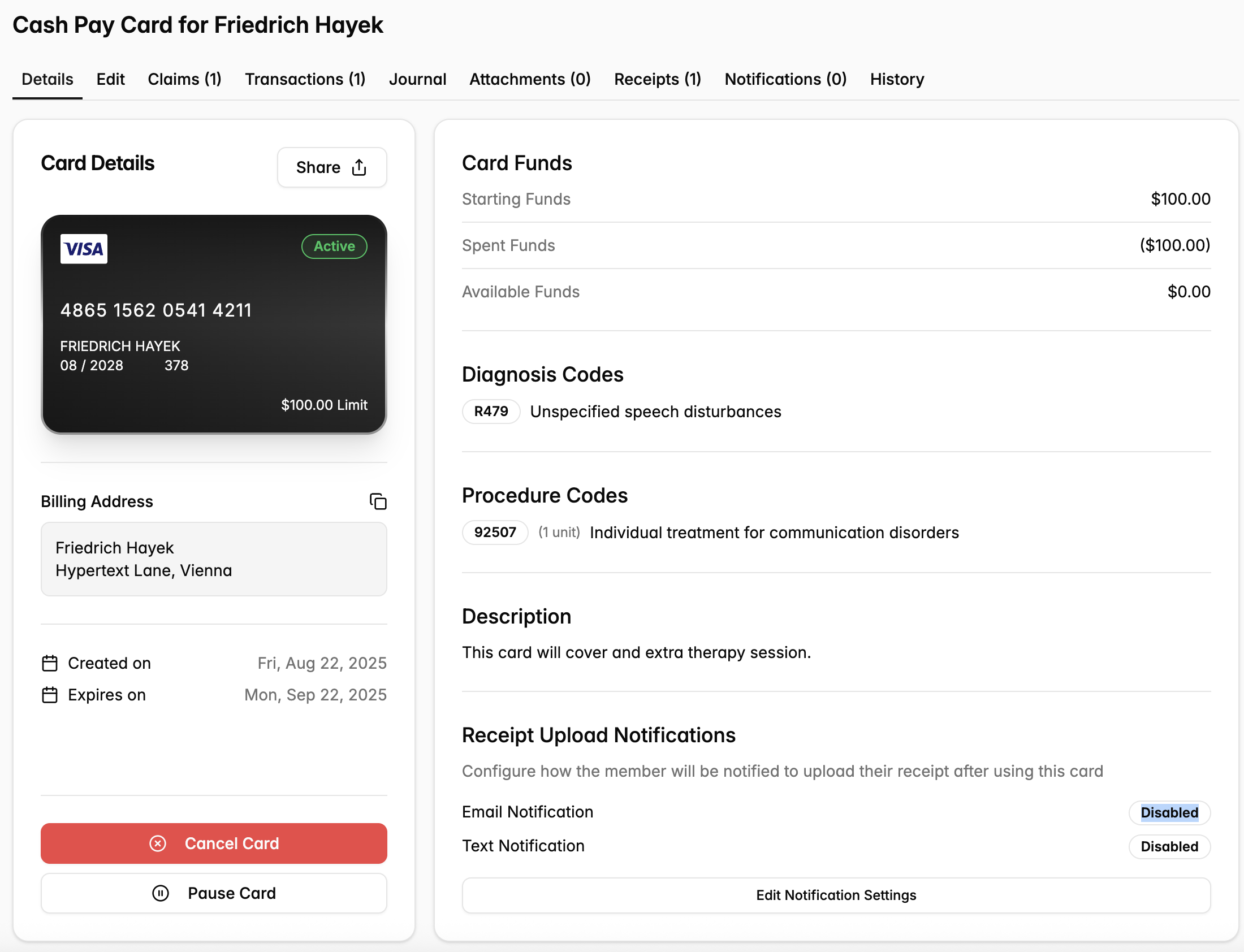

Every day, Yuzu enables hundreds of “on the spot” decisions made by care navigators, direct primary care doctors, and members. We do this through our collaborative software where care navigators are empowered with permissioned cards they can use to transact healthcare that makes sense using knowledge The Algorithm will never have.

We process hundreds of decentralized healthcare transactions like the above each week. Our role as a health insurance TPA is to let information and money flow to enable the plans we support to purchase efficient healthcare for their members.

Our mission is to build a system that lets strangers take care of each other. See our open jobs here.