In a not-that-alternate alternate universe, I would be a math professor studying something like game theory. Game theory is the study of incentives and how incentives can shape how people and organizations interact with each other. Game theory is a popular approach to studying social and economic problems and designing how markets should work.

The game theory approach to answering social problems is to model the incentive functions of the agents whose interaction you want to study and then solve for the optimization functions of these agents under various conditions.

Game theory can reach some pretty interesting results about human behavior through very basic assumptions and 5th grade math.

There have been many economics and math papers on such simple games as the famous "prisoner's dilemma".

Providers have perverse incentives that cause them to provide unnecessary care, keep referrals within a hospital system, and practice defensively to avoid litigious suits. Payers' perverse incentives cause them to add friction to members who need to access care, find reasons to deny claims, and invest in risk-selection rather than care procurement.

What intuition about healthcare economics can we learn by studying the math behind incentives? Quite a lot!

Exercise 1: Prisoner's Dilemma

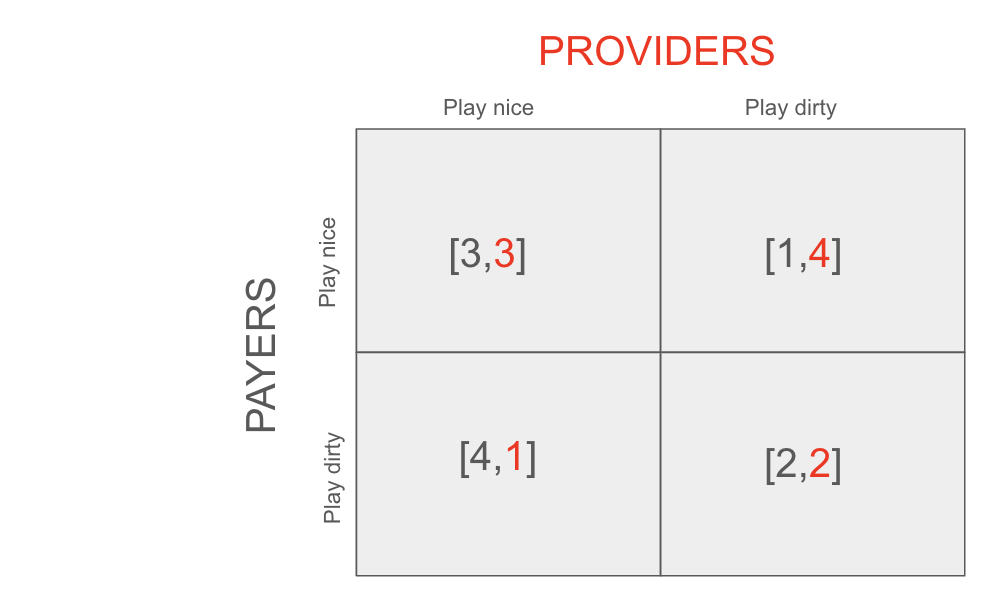

Let's start with an easy game. The prisoner's dilemma. You've probably learned about this at some point. The matrix presented here has the same general payout matrix structure as all prisoner's dilemma games.

Setup: Providers (red) make a choice "Play nice" or "Play dirty" represented by the left and right columns and receive RED payouts. Payers make the same choice represented by the top and bottom rows and receive BLACK payouts.

This is modeling out how a provider interacts with a payer in a single claim-generating situation.

Each has the choice of "Playing nice" with each other or "playing dirty" with each other.

Providers play nice by only recommending necessary treatment and cost/quality balanced referrals.

Payers play nice by paying claims quickly and completely and not requiring the provider to submit burdensome documentation.

If both the provider and the payer play nice, they will both pay/be paid a fair amount and spend nothing on legal or claim review.

If the payer plays nice but the provider plays dirty, the provider will be able to sneak in some subtle upcoding and improve their payout.

If the provider plays nice and the payer plays dirty, the payer will be able to justify delaying paying claims due to insufficient documentation.

If both play dirty, they will achieve a fair outcome but both spend a lot on legal and claim review.

Analysis: there is only one Nash Equilibrium for this game, and it's that the two parties end up both playing dirty.

Assuming the other side plays dirty, both sides would get a better payout playing dirty than playing nice.

It's surprising but completely logical given the constraints and incentives of the game that the outcome achieved in the Nash Equilibrium has the least total utility (total = 4) of the 4 possible outcomes.

This is why it's called a dilemma, after all!

It probably explains a little bit of intuition for why healthcare sucks.

Important Note: The order of who "plays first" does not matter in this game. I have been describing scenarios as if the provider decides to "play first" but the results hold either way and in general it is assumed that both players make their decisions separately but with complete information about the game including the other player's incentives.

Exercise 2: Expensive Fights

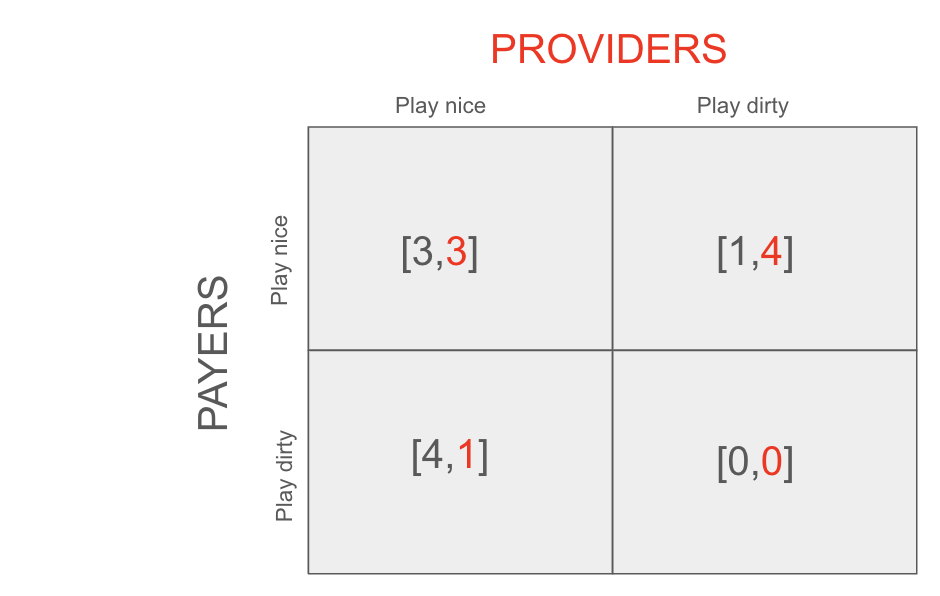

While the payout matrix in Exercise 1 probably approximates how large claims are treated in healthcare, for small-dollar claims the matrix is probably a bit different. In particular, the relative cost of admin work custom to a single small-dollar claim is higher (smaller portion of total).

This changes the game theory dynamics in a fun way. The payout matrix is no longer one of the prisoners dilemma variation.

So let's analyze the payout matrix below that represents this situation

Top right and bottom left are Nash pure Equilibria. They both have total utility five.

Analysis: the payout matrix here has two pure Nash equilibria.

#1: Provider = nice, payer = dirty

#2: Provider = dirty, payer = nice

It also has a mixed equilibria:

#3: Payer and provider both 50% nice.

#1. If the provider plays nice (left row) the payer (gray) is better off playing dirty. But given advance knowledge of the payer doing this, the provider can't get themselves to a better situation by changing their mind and playing dirty too (since bottom right is 0 payout). So this is a Nash Equilibrium.

#2. If, on the other hand, the provider plays dirty, the payer is better off playing nice since otherwise the amount of admin work required to justify a claims denial and handle potential appeals outweighs the cost savings. Neither party can better their situation by changing their mind here, proving that top right is a Nash Equilibrium.

Let’s mix it up!! The third Nash Equilibrium is more complicated and involves both parties making decisions probabilistically. See video below.

#3: In the third case (the "mixed strategy") solution, the payer and provider both choose to randomize playing nice and playing dirty 50% of the time.

I'll skip the proof that this is a Nash Equilibrium (check out the video for more). But it is. Neither party is able to tweak their strategy in response to a 50% probabilistic strategy from the other party.

The total utility here is the average of the four equally likely squares total utilities which equals 4 in this case. This is lower than the utility of the pure Nash Equilibria, but that could be reversed if the [Nice, Nice] option had greater utility for both players (e.g. [10, 10]).

A few takeaways for healthcare:

The "mixed strategy" case can be thought of as simulating when to do randomized claim review (a common practice for smaller bills for both payers and providers).

Since this game is played many times between new payers and providers interacting for the first time, its bleak outcome explains why many payers and providers alike feel like the other party is untrustworthy.

In reality, billing doesn't exactly work like this since payers and providers know each other. We will handle this exact situation in the next section.

Exercise 3: Engineering Cooperation through Repetition

The situations we described above lead to bleak outcomes. How do we engineer trust out of a system like this?

Well obviously it's hard, since this is an unsolved problem in healthcare. But Game Theory does have some insights here, and that has to do with "repeating" the game over and over again.

This is something that happens in practice in healthcare, where payers and providers will develop trust with each other through processing many claims together.

The video to the right explains the dynamics of repeated games, including how strategies in these games devolve into concepts like "punishment" of defection and a simple, experimentally optimal strategy of "tit-for-tat" that defaults cooperation but is able to punish defection.

I am not better than Veritasium at explaining things, so I'll leave it to him. But this video is required watching.

Homework, Exercise 4: What about the patient?

The patient has different incentives than the payer or the provider.

The patient's incentives sometimes align with payers and sometimes with providers.

Example: patients don't like the paperwork that payers throw onto them, but they don't benefit from over-treatment (which oftentimes has negative medical side effects, and financial implications for patients with high deductibles).

The payoff matrix for three participants is a cube (2x2x2).

The video to below is a good starting point for thinking about these situations.

Addendum: The Minimax Theorem

To be written.

Takeaway #1: The "claims adjuster" and the "network" profit from the broken system.

If you were following the "hints" in the exercises above, you may have noticed that the loss of utility loss for providers and payers was picked up by "claims adjusters" and "networks" who do the work of negotiating billing amounts that are fair.

These people should not be necessary, but since providers and payers don't naturally have incentives that align in a Nash Equilibrium in the current system, these people have plenty of profitable work to do (that doesn't benefit patients overall).

Takeaway #2: Change the game, not the players

You can design a health plan that changes these incentives and their corresponding payout matrices if you understand how to reason through how incentives will change the strategies of the players in the game.

Yuzu Health partners with plan designers that invent new strategies and want to deploy them.