Context: A good thread in the Out of Pocket Slack community prompted a discussion about different types of health insurance plans.

The world of health benefits has gotten remarkably confusing in the last 10 years, and there are a lot of styles of health insurance plans in the market. In order to explain this complexity, it helps to actually think about the problem from first principles and understand the order in which various types of health plans actually developed.

The right framework to have is this: healthcare should be simple and used to be simple. It only got complicated because of bad incentives (for all players involved) and the many "innovations" in healthcare that tried to reduce cost but ended up increasing complexity.

It's confusing out there. But health plans were meant to be simple. Their simple problem is to "get people the care they need at a reasonable price that they can understand". Don't forget this problem as you think about "solutions".

Employer-Sponsored Insurance Can Be Pretty Much Anything! Fun! Scary!

Employers who self-fund their health benefits have a lot of flexibility in deciding what their health insurance plan looks like. This is thanks to a federal law called ERISA which pre-empts most state laws and protects employers' rights to design their own health insurance plans.

The ACA and other laws (MHPAEA, NSA, etc) have come in and regulated some aspects of these plans, but they have not touched the fundamental right that employers have in designing their own health insurance plans.

This section goes through some edge cases. It's important to understand the edge cases of any problem before diving in to understanding "solutions" to that problem.

1. Businesses can just declare benefits.

As a business you can just "declare" benefits to your employees and their qualified beneficiaries. You don't legally have to "buy" an insurance policy from anyone.

We did this at Yuzu Health. We didn't buy stoploss insurance or get access to a network. I just signed a document and suddenly everyone had insurance.

There are some constraints you have to follow.

Your benefits must be fair to all employees. You can't just give benefits to employees that are buddies with the CEO. You can't just give benefits to employees that are healthy (HIPAA actually was the first law that required this). You CAN discriminate against part-time and full-time employees (see the ACA for details). You can also give different benefits to people who work in different locations. There are some other edge cases here too.

You must comply with reporting requirements (to the IRS) under Section 5500.

If you offer some benefits, you have to offer other benefits. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act for example says you need to offer mental health benefits that are "as good" as your physical health benefits.

You must tell your employees what their benefits are. This requires giving them a Plan Document and Summary Plan Description (SPD).

The way in which you adjudicate claims has to be fair (but you can totally just do this in-house if you want). There are many laws and regulations regarding this, mostly governing how quickly you have to pay a claim and how much explanation you have to give if you reject a claim.

2. Businesses don't even (really) have to cover anything.

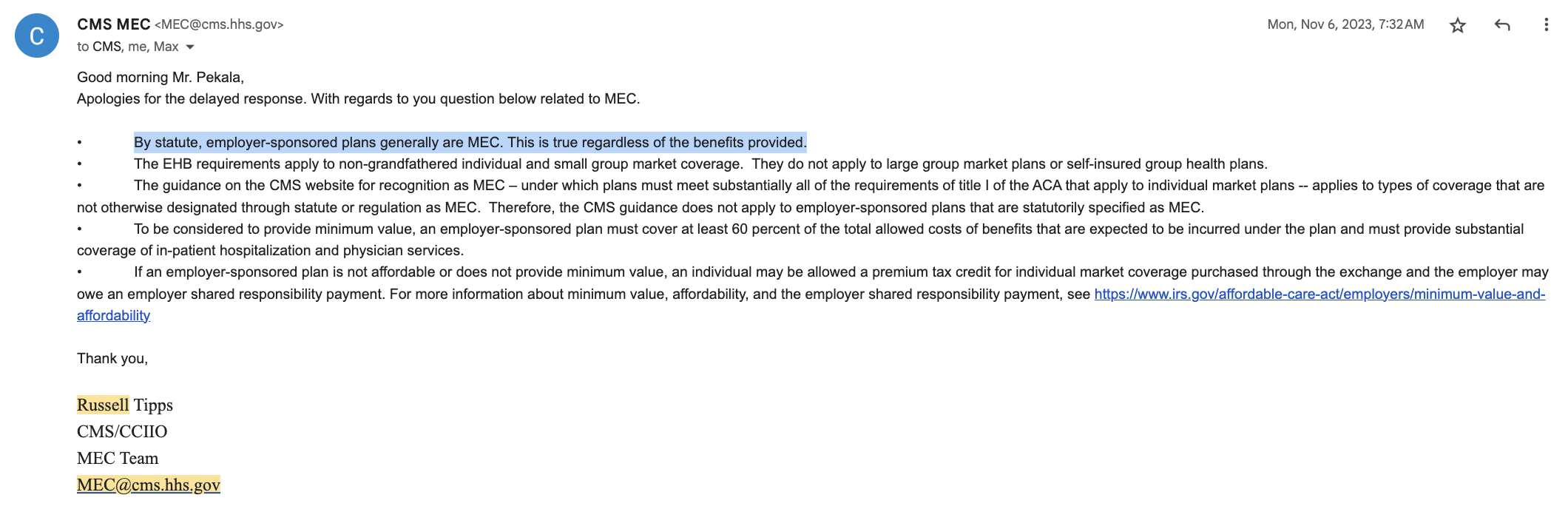

It's surprising to many people that technically speaking, employer-sponsored health insurance legally doesn't have to cover much. In fact, there are many plans (deemed "MEC" plans) that exclude all hospital benefits and only cover ACA-required preventative care. They market themselves as "ACA Compliant" and cost ~$50/month.

The ACA designated that certain employers (>50 FTEs) could face tax penalties for not providing plans that were deemed to have "minimum value", itself a nebulous term that is based on an actuary's assessment of the plan's expected value (e.g. claims paid) versus its costs (premiums). Actuaries are good at lying with numbers though.

Businesses also don't have to buy stoploss insurance to offer self-funded benefits. This means they could "declare" benefits that might cost them millions of dollars to pay, but don't have to actually have to prove that they have the money to pay these claims. If they don't have sufficient insurance to pay these claims, the business would go bankrupt and the claims against it might not be able to recover the full amount owed (leaving members in debt to providers).

3. Businesses can write whatever in their plan documents. Even things not legally true.

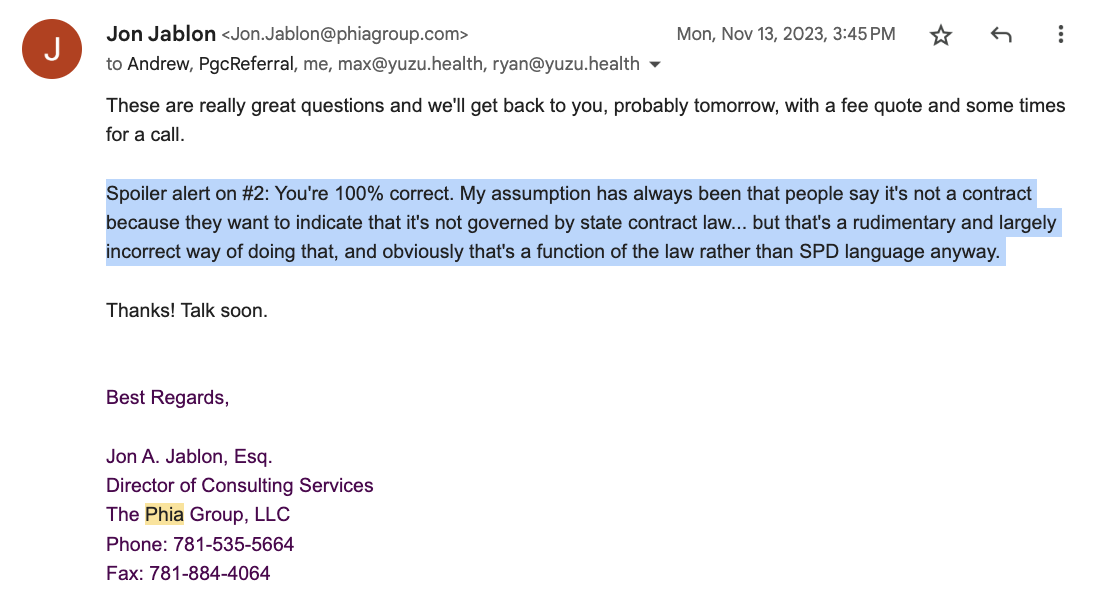

Plan documents are legal contracts. But the industry-standard lawyers we contracted to help us draft our plan documents had a provision in their plan document templates that stated that the plan document was "not" a contract.

I asked about this below and they basically said that yes, plan documents are still contracts but by stating that they are not contracts in the plan document it might help avoid various state laws.

I've also seen other things stated in a health insurance plan document that are not legally enforceable (e.g. that insurance pays after hospital financial aid).

Healthcare is confusing. But mostly because it's filled with loopholes. It's filled with loopholes because it is so highly regulated.

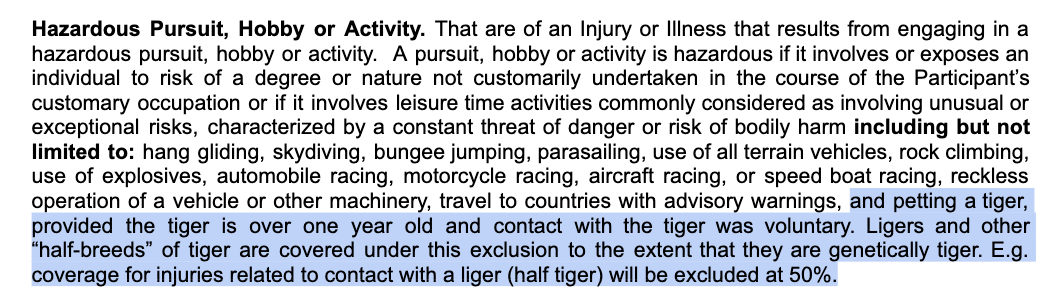

Another funny example of writing whatever you want in a plan document is as follows. A common plan document exclusion is for "hazardous activities". It's legal and common to exclude things like skydiving, shark breeding, whatever. I wrote in a custom exclusion for petting tigers (see below) into the Yuzu plan (for internal employees). This is perfectly legal.

I sent this plan document to many, many people (lawyers, stoploss carriers, etc). Only two noticed this crazy provision. Yuzu hired one of them.

Summary: health insurance plans cover whatever is in the plan document. They are subject to many regulations, but there are loopholes for virtually all regulations.

I'm a Good Employer. Help Me Set Good Benefits

From here on, we're done with evil edge cases and we are going to assume that you want to design a good health insurance plan for yourself and your employees.

There's still a lot of work to do! Let's go through what I think would be a natural way to approach this problem from first principles. "First Principles" doesn't mean doing what everyone else does!!!

You can just pay everything! Problem solved, right?

If you want, your policy could just be that everything is covered. Perhaps, you don't even require any documentation of claims.

On the first day of eligibility, one of your employees could just file a claim for a million bucks and say that it was for a doctor visit.

Now you're out a million bucks. There's nothing you can do if you didn't have proper claims procedures in your Plan Document, since it's a legal contract that binds you to provide those benefits.

You could try fixing this problem by specifying in your plan document that you only pay claims that come with supporting documentation from a licensed doctor.

But perhaps one of your employees has a sister who is a doctor owning her own practice, who submits a claim for a million bucks to the plan, expecting payment.

What do you do? You could go to court, but courts would probably examine your Plan Document and say that the contract obligates that you pay the member's claim. The member followed the instructions in the plan document and had a technically eligible expense.

Frustrating. Contracts are tricky.

Okay I can't pay everything. What should I do?

The historical solution to this problem was to invent the concept of "network".

The idea behind this is that the Plan (e.g. the Employer) would find a bunch of trusted providers who would bill fair amounts and only accept claims from those trusted providers.

They would write this information into their contract (the Plan Document) and would be able to avoid the problem above.

Hypothetically, this doesn't actually require that the Plan has a contract with any providers, or even notify the providers in any way that they are deemed "in-network" according to the plan. The health insurance plan document is a contract between the insured Employee ("subscriber") and the company.

Of course, this still exposes risks. Suppose that some "in-network" but non-contracted provider gets wind of this arrangement. It would be awfully tempting for them to just submit claims to the plan willy-nilly.

Now we've reverted back to the above issue where the plan is obligated to pay a theoretically infinite amount.

Okay, I have a "network" of providers and have contracts with them. Am I good?

Yeah, this is pretty much what every health insurance plan does.

There are many issues with this solution, though.

You are a business, and you don't really have time to reach out to providers and contract with them.

You don't know how to sign contracts with providers. There are many "gotchas" in these contracts that could easily be the subject of another blog post.

Now administering benefits is confusing. You have to keep track of which providers are in your network, and at what rates, and educate members about this.

You can't easily add providers to your network, even if those providers want to offer care to your members at good rates.

What ends up happening here is that third-party companies end up managing the networks of providers. Employers typically pay these companies a "Per Employee Per Month" (PEPM) fee for doing so. Sometimes they pay a percentage of savings.

The most popular companies that do this are Unitedhealth, Aetna, BCBS, etc.

There are the so-called "regional networks" as well that are strong in certain areas. These include MagnaCare (New York City focused), and Ohio Health Choice (Ohio focused). And national rental networks like PHCS (owned by Multiplan).

Note: networks are not insurance companies. The self-funded employer is still the "insurance company" here. But the network contracting company defines which providers are in network under the employer's Plan.

How do I know if my network is any good? How big should my network be?

There is a whole class of people who are above-average at Excel who would be happy to charge you a few grand to pull a few bar charts to help you understand how good your network is.

It's a hard question to answer.

Especially since "good" means different things to different people. Some employers might be most concerned that their network is too expensive, while others might be more concerned with whether their network has enough providers in it.

You generally do get this tradeoff. Richer network, higher costs. Not every provider will want to contract with you if you don't offer enough dough.

There is no perfect answer to the question of how rich your network should be and it depends on the preferences and needs of the entire group.

Of course, there is also a lot of greed and bad incentives in the current system, not stemming from philosophical questions questioning how rich your benefits should ideally be.

Networks hire sales teams. These teams are incentivized to only tell you about how strong and affordable their networks are.

If you're an employer who isn't good at doing provider contracting, how are you supposed to be good at evaluating provider contracts?

Shockingly, until Trump's No Surprises Act, there was no legal obligation for networks to even provide information on their contracts to Plan Sponsors or Plan Members at all.

The No Surprises Act legally just requires that insurers (e.g. Plan Sponsors) disclose their network rates to Plan Members, instead of requiring that networks disclose this information to insurers. However, since this information has become more public, it has influenced network choice decisions as well.

Give me a super easy way to think about network strength.

Sure. Marketing people can do this for us.

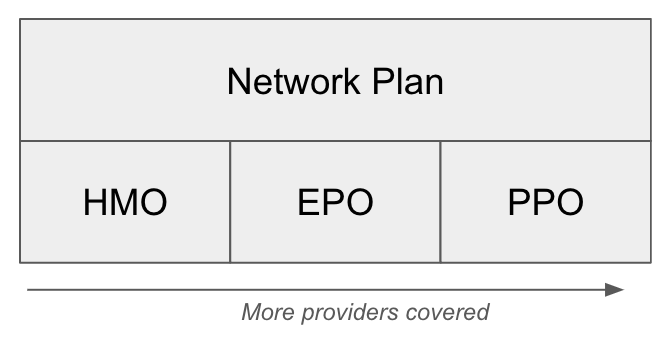

The common words are "HMO", "EPO", and "PPO".

HMO stands for "Health Maintenance Organization". The classic example of an HMO is Kaiser. This type of health insurance plan was popular during the "managed care" decade of the 90's. Kaiser is still popular, and United and other carriers offer HMO-branded plans to this day.

EPO stands for "Exclusive Provider Organization". These types of networks are typically built around one local health system. In exchange for good rates at this one health system, members are steered to stay within this health system with other care being out of network.

PPO plans are currently the most popular. They allow access to the broadest range of providers in network.

There are additionally a ton of random plans labeled things like "EPO Plus" and "HMO Select" that just add nice sounding words after PPO/EPO/HMO for pizazz.

The terms HMO/EPO/PPO don't technically mean anything. They are more marketing labels than anything else. I could call myself a PPO without having any providers in network and I don't think anyone could sue me.

Alright, this Sucks. Let's Solve the Provider Contract Problem with More Contracts

If you made it this far, congrats. The industry got here about 10 years ago, once it realized that networks (no matter how narrow or broad) didn't allow them to deliver better and cheaper benefits over time.

The solutions that it came up with were two-fold:

"Direct Contracting".

"Tiered Networks".

I'll explain each of these two solutions below, but keep in mind that both of these are essentially just putting a band-aid on bad contracts with more contracts.

If you're a lawyer, your mouth is watering up right now with the amount of fees this "contracts on contracts" world has in store for you.

Direct Contracting

Direct contracting is roughly when an employer of sufficient (usually large) size decides it can go ahead and negotiate with a hospital in its area by itself.

Usually (almost always) these direct contracts are between one large employer and one large hospital system. The employer typically doesn't replace the network they were already using, they just carve out one hospital system and get their own rates there.

There are significant problems with direct contracting.

Only large employers can do this, since it's not worth the hospital's time to contract with a small employer who won't even have that many patients sent their way anyways.

This will likely be against the terms of your existing network contracts (which you got from a third-party mentioned above). You will need to renegotiate these contracts now, and they won't be happy.

More lawyers. Always a problem.

I'm not saying that direct contracts don't work in certain situations, but they are not fundamentally a different approach to the problem of giving members affordable care at predictable prices.

They still utilize contracts as their basis, and really just claw back some of the work of doing those contracts to the Employer.

Tiered Networks

Tiered networks take a different approach. With direct contracting, the only difference to the plan will be how much the Plan pays at providers directly contracted.

As a member, you might not be able to tell whether your Plan is utilizing direct contracts or not, since it doesn't affect who is in network or how much you pay for that provider who is in network.

In a tiered network plan, the provider network stays untouched, but a new network is added into the plan.

Typically this new, added network

Has lower costs to the Plan for services provided within this network.

Tries to incentivize members to go to providers in this tier by offering lower copays, lower deductibles, or generally more access to care (e.g. "on demand virtual doc").

Having a tiered network in your plan design might still put you at risk of breaking contract terms within your original network (they don't like that you are planning to use them less, especially if you are paying that network a percentage of savings or some other usage-based fee).

What if Contracts don't Make Healthcare Better?

If you get the feeling that this network thing is all some sort of dumb game, you're not wrong.

Somewhere RIGHT NOW (if it's before 4:30pm CST) there are old guys in suits laughing at you from an office building in suburban Minneapolis. Laughing because Unitedhealth has all the contracts, and you keep paying them for sitting on secrets, unable to build trust with your own employees without them.

Let's go back a few steps and see if we can solve the original problem without needing to invent networks to do so. The original problem was that we need a way to pay a reasonable amount for care that members need, without opening us up to being liable to pay unreasonable claims.

Instead of inventing a network, there is another fork we could have chosen: that of "reference pricing". In a Reference Based Pricing (RBP) plan, members don't have a network. Instead, they have a service-specific allowed amount for any type of eligible service.

Note: this isn't that revolutionary of an idea. It is actually how many network-based plans adjudicate out of network claims.

They typically first "reprice" the claim to their "non-contractual allowed amount" using data about what that service typically costs. Then they compute how much of that claim is covered by your cost-sharing (deductible+coinsurance+copay) and pay the rest.

The word that they typically use for determining this "non-contractual allowed amount" is the "Usual and Customary" amount. For reasons I won't go into, this number/amount can be gamed and hard to compute. But philosophically, assuming the existence of a way of figuring out how much claims should cost this could be extended to be a pretty good way to pay for all claims, not just out of network claims.

That's essentially what Reference Based Pricing does.

Typically the "reference price" is what Medicare pays for such service. This reference price (when defined) is public since Medicare is public.

There are issues with using Medicare as the reference price. Since it is a program for senior citizens (and people with CKD), its rates are not representative of the basket of services younger populations would purchase.

Also, typically Medicare gets a much better rate than commercial payers could ever hope to get. So commercial payers must adjust the rate they are willing to pay to be between 120% and 200% of Medicare to ensure that their members have sufficient options for Plan-covered care.

Offering only Medicare prices to providers ("Medicare for all") would result in a lot of balance bills and angry providers.

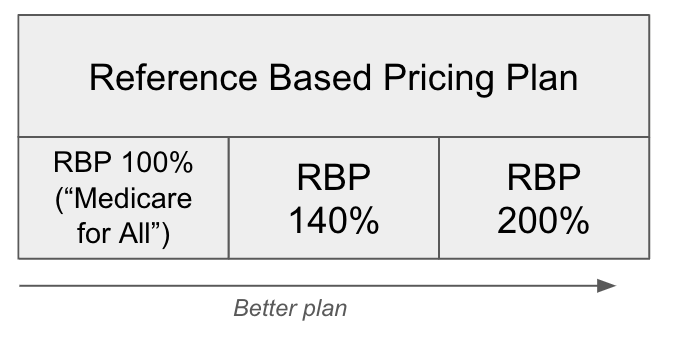

The diagram below is the counterpart to the HMO/EPO/PPO diagram from earlier.

Plans can change their "allowed amount" (and thus the number of providers accepting that payment) by simply dialing up or down the percentage of Medicare that they are willing to pay claims at.

This is pretty awesome. Just by changing a number in a plan document, you can effectively add more providers to your network without having to go out and contract with those providers!

Fewer lawyers. On the frontend at least.

Problems with Reference-Based Pricing

Balance billing. Network plans ensure that if a member goes to a provider in network, they will only be billed the contractual allowed amount. If a member goes to a hospital or ER that is not in-network, they could in theory be billed virtually anything yet have the plan only pay up to some percentage of Medicare. The remainder would legally be money that the member owed to the provider that the provider could balance bill the patient for. This can also happen in a network setting with out-of-network bills too, but is more common in RBP plans.

Difficult use. It's harder for members to use their benefits since many providers will not see members who don't have a logo the front desk person understands on their health insurance cards.

Difficult to explain. It is difficult to explain this style plan to members, since the plan designer won't know exactly which providers accept payment at various percentages of Medicare. These prices are not posted by providers (usually since they don't want to give up leverage in their network negotiations).

Solutions to these problems

There are several solutions that partially fix these problems.

"Concierge" steerage. Adding in a solution that can help steer members to providers that are known to bill within the appropriate range can help members avoid balance bills and help members schedule appointments.

Cash-pay. Instead of having members give the front desk person their insurance card to pay for care, you can have members ask for the cash-pay price. Most of the time, outpatient care is well within 150% of Medicare for cash-pay patients (since it is less paperwork for providers).

Advanced EOB features for reference pricing. If you can provide a way for members to look up how much their service would be paid at, then they would avoid having a surprise bill come after the fact.

Example plan

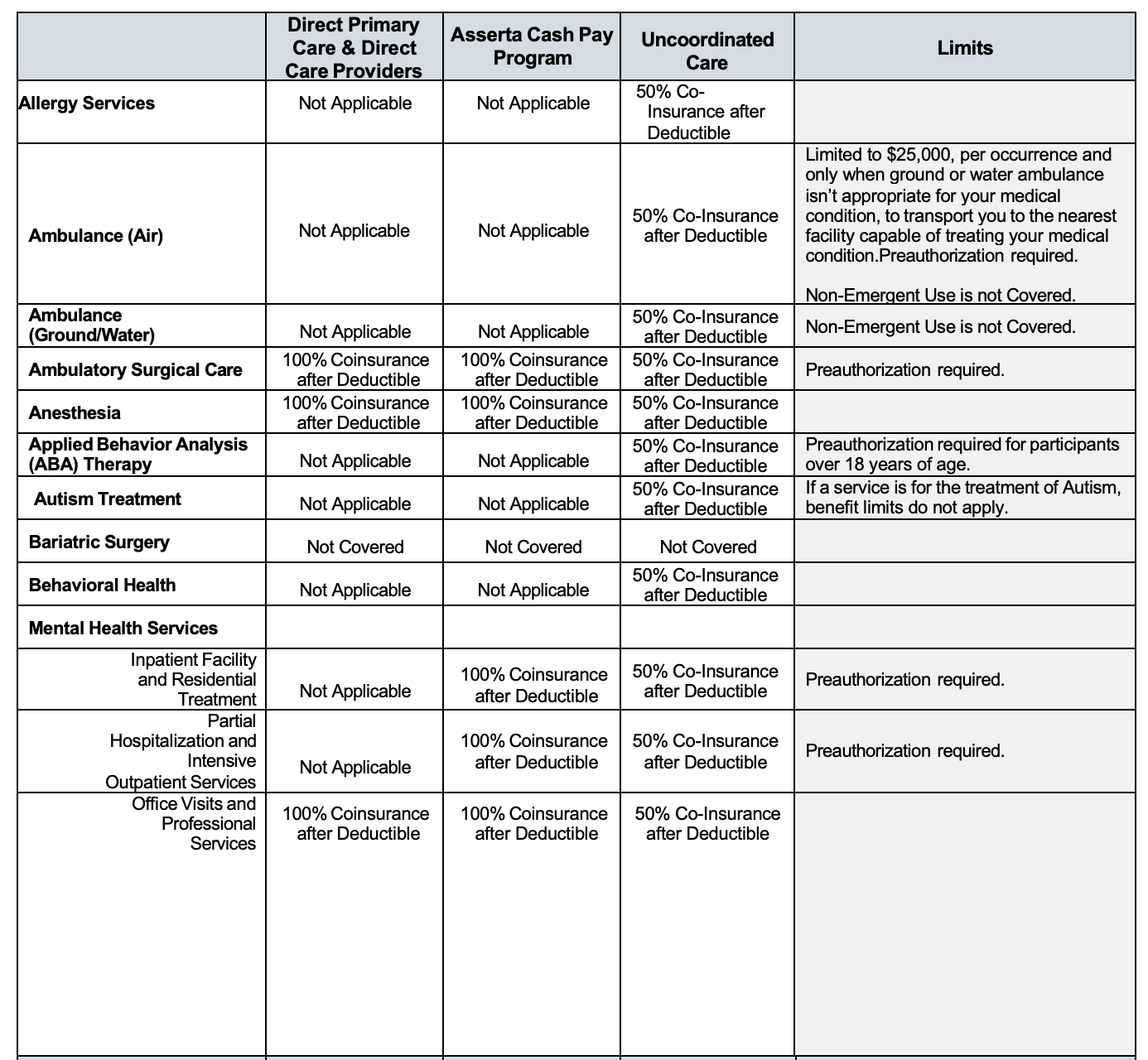

The plan ← (expert from SBC) has a few benefit tiers, but no traditional network. Instead, it has a Direct Primary Care layer (capitated care) that members can use for primary care combined with a navigated-care layer where the navigators are aware of the 150% of Medicare restriction to how the plan pays benefits.

For benefits not "coordinated" by the navigation layer or performed by the DPC, the plan pays 150% of Medicare.

Planned hospitalizations can be handled by care-navigators, who are often able to find providers and negotiate case agreements on an ad-hoc basis.

Summary

Effective plan styles are complicated and evolving.

Network style plans no longer guarantee good rates at predictable prices like they were designed to. The next plan style seems to be reference pricing, but it is still in its infancy and deemed too experimental for many brokers and plan sponsors to try out.